Mass Shootings and the Conversations They Evoke

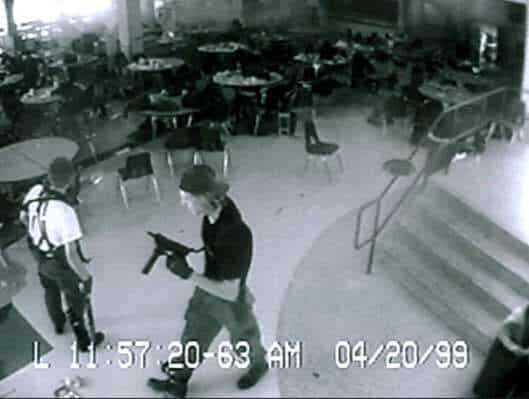

Eric Harris and Dylan Klebold, on Columbine Highschool Security footage, moments before taking their own lives.

Sean Stoker | Opinions Editor | @theroyalthey

It has happened once again. We find ourselves in the aftermath of a seemingly random act of violence. Dylan Roof, a white 21-year-old man, attended a Bible study at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church, a historic building with several ties to the American civil rights movement, and gunned down nine churchgoers, wounding a 10th. It seems to be just one more horrid addition to a long line of horrific mass shootings to which America has been subjected in the past several years.

We as a society are more aware of gun violence and mass shootings than ever before. This is not to say that they have increased as of late, as the peak of mass shootings in the United States was in 1929, according to data from criminologist Grant Duwe of the Minnesota Department of Corrections. But due to the omnipresent technology that we all carry in our pockets, we are made aware of every incident soon after it happens.

Regardless of how common or uncommon these incidents are, each and every one is a tragedy, and should be treated as such. Communities are torn apart. Families are devastated. And lives are violently brought to an end long before their time.

It seems that every time these tragedies occur a relatively small amount of the conversation is about the human lives impacted. The majority of what we say is to politically grandstand, or make loud demands for sweeping and immediate legislation.

This is, quite frankly, disgusting.

We, as rational human beings, see a problem and want to fix it. This is an impulse that comes from a good place, but our efforts to express it are often misguided. There is nothing wrong with taking measures to prevent a tragedy, but there needs to be some sensitivity in our approach to the situation.

After the horrific events at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown in 2012, as a nation we were sickened, horrified, that 27 lives – 20 of them grade school children – could be ended so quickly, so brutally.

And then, before the dust had even cleared, a war of words, almost as violent as the actual event, broke out in the comment section of every news outlet over why this incident should be used to support gun control, or how the death toll could have been reduced if only one of the teachers had been carrying.

The gun debate, though certainly not started by the Sandy Hook shooting, has gained a considerable amount of steam in its wake, and the wake of other tragic events like it.

Launching these debates so quickly and flippantly is not only contentious; it is tactless and insulting to the victims and their loved ones. It sends the message that you care less about them, and more about political views.

The real debate we should be having is what to do for the mentally ill. Adam Lanza the perpetrator of the massacre at Sandy Hook, was diagnosed with a sensory-integration disorder, obsessive-compulsive disorder, and Asperger’s syndrome, and was suspected by family to also have schizophrenia and some form of psychopathy.

James Holmes, who fired into a movie theatre in Aurora Colorado the same year, was seeing three psychiatrists and communicated to a classmate that he may have dysphoric mania.

Seung-Hui Cho, perpetrator of the 2007 Virginia Tech shootings was said by a doctor to be “mentally ill and in need of hospitalization.”

Eric Harris and Dylan Kleibold of the infamous Columbine massacre were respectively psychopathic and depressive.

Does anybody sense a pattern?

Every time I suggest this be the topic of conversation however, I’m accused of being a gun-lover. While I have no strong opinions on the second amendment—whether or not you like guns, I won’t judge—I have personally lost a loved one to the dangerous mixture of guns and mental illness, so they aren’t exactly something I cheer for.

But sadly, I fear we won’t be able to have the intelligent conversation these shootings deserve, at least not in the current socio-political climate. We want immediate results, and campaigning to help the mentally ill and/or drug addicts isn’t something that does that. It takes time, and how do you help the 61.5 million Americans with mental illnesses when it’s so difficult to help just one?

The science of treating mental illness is still in its infancy. We’re only 130 years from the dawn of Freud’s psychoanalysis, and a measly couple centuries from adjusting people’s humors. We’ve still got a long way to go in pinning down the mysteries of the human psyche. Why would our public conversations delve into such deep territory when guns have been around for over 1000 years?

No, instead we’ll argue about guns because they are more tangible and easier for our minds to grasp. The concept of a mental disorder is abstract, something we can’t physically regulate, whereas a physical object like a gun is, ironically, an easier target of our debates.

I leave the solution to you, dear reader. If you or anyone you know is troubled, or in any way mentally or emotionally unhealthy, get help immediately or reach out to the afflicted. In the end, we all need to be heard.

National Alliance on Mental Illness (NAMI) of Utah County: (801) 492-4443

Crisis Line of Utah County (Orem): (801) 226-4433

Wasatch Mental Health (Provo): (801) 373-7393